How did the universe originate? Why do we exist? And why is there nothing? They are the big questions of physics that the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Meyrin, Switzerland, is researching. Of course, the final answers to these questions are not yet known, but many others have been found here – after all, even the World Wide Web began at CERN.

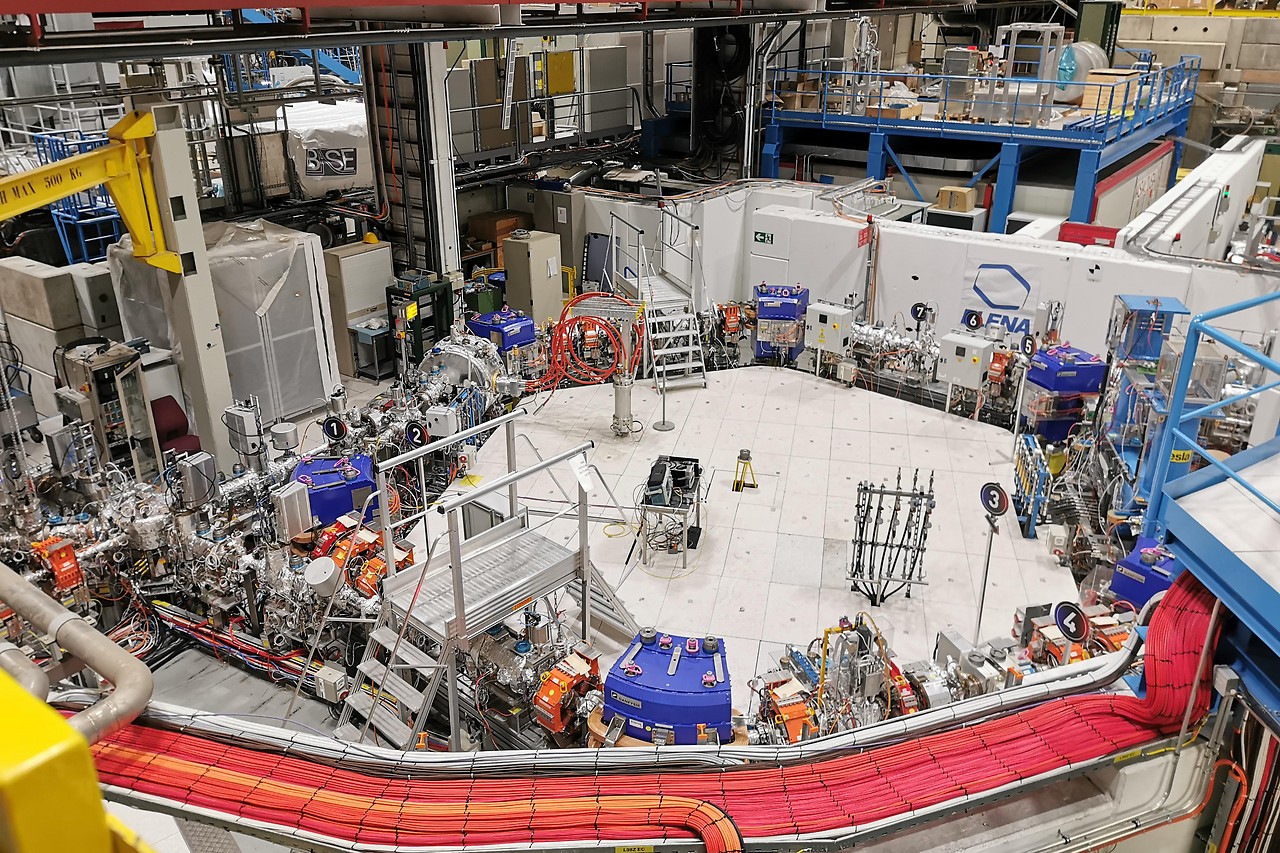

It is difficult for ordinary people to understand exactly what is happening there near the French border. The smallest particles are accelerated to nearly the speed of light and then collide with other particles filled with energy. This happens more than a billion times per second at the Large Hadron Collider, the core of CERN – a ring-shaped particle accelerator with a circumference of 27 kilometers.

It is therefore not surprising that the visit to the “Particle Physics Mecca” stunned an entire delegation. When a delegation from Lower Austria visited this week, the main focus was on forward-looking cooperation. After all, CERN has been “an important partner when it comes to innovations, especially in the medical field” for years, asserts Governor Joanna Mikl-Leitner (ÖVP).

The insights gained from the above collisions should ultimately not only answer the big questions of physics, but are currently used primarily in medicine. “An important part of our mission is to transfer knowledge and technology to other areas and to maximize the social impact of our research,” says Mike Lamont, director of accelerators and technology at CERN.

Cooperation with CERN enters the next round

Cancer patients in Austria have also benefited from this since 2016. Since the start of MedAustron in Wr. Neustadt has already been treated with ionizing radiation. Compared with conventional radiotherapy, these ion beams can be better controlled, which is why tissues surrounding tumors are damaged less. This makes it easy or even possible to treat tumors in the brain and near the spinal cord. More than 500 treatments are expected this year.

But it wouldn’t be CERN if we weren’t constantly working on new, better apps. Together with Governor Michael Leitner, MedAustron General Manager Alfred Zenz and partners in Italy – the National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN) and the National Center for Molecular Therapy (CNAO) – two additional cooperation agreements for the coming years were signed on Wednesday. “It’s about sharing scientific expertise and generating more innovation from it,” says Michael Leitner.

The SIGRUM project aims to revolutionize cancer treatment

Great hope for the future is the so-called SIGRUM project. In this case, SIGRUM stands for “a superconducting giant with unconventional Riponi mechanics”. The point of this technology is that we want to rotate the ion rays around the patient. We want to irradiate the patient from different directions in order to treat his tumor,” explains Alfred Zenz, MedAustron’s Managing Director.

To date, there are two treatment rooms at MedAustron in which irradiation is carried out with fixed beam lines – both horizontal and vertical -. A third treatment room will be operated in the coming weeks. Even this should allow radiation from different directions. SIGRUM should go one step further and enable this comprehensive irradiation not only with protons but also with carbon ions.

This means further improvement for cancer patients. “We want to develop the next generation,” says Zenz, “stronger and more economical.” Of course, such a development is not possible overnight. The “nice” thing about this development work, however, is that intermediate steps can indeed be incorporated into existing treatment options. “This means that we will be experiencing year after year how everything is getting better faster and how we can treat different, different types of cancer,” Zenz says.

“Total coffee aficionado. Travel buff. Music ninja. Bacon nerd. Beeraholic.”

More Stories

The European Space Agency announces “signs of spiders on Mars”

Raising diamonds made easy – Spectrum Science

Everything related to prevention and treatment