In the process of merging supermassive black holes, a new way to measure the vacuum

Scientists have discovered a way to determine the “shadows” of two supermassive black holes during the collision process, giving astronomers a potential new tool for measuring black holes in distant galaxies and testing alternative theories of gravity.

Three years ago, the world was stunned by the first image of a black hole. A black hole of thin air surrounded by a ring of fiery light. This is the iconic image of[{“ attribute=““>black hole at the center of galaxy Messier 87 came into focus thanks to the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), a global network of synchronized radio dishes acting as one giant telescope.

Now, a pair of Columbia researchers have devised a potentially easier way of gazing into the abyss. Outlined in complementary research studies in Physical Review Letters and Physical Review D, their imaging technique could allow astronomers to study black holes smaller than M87’s, a monster with a mass of 6.5 billion suns, harbored in galaxies more distant than M87, which at 55 million light-years away, is still relatively close to our own Milky Way.

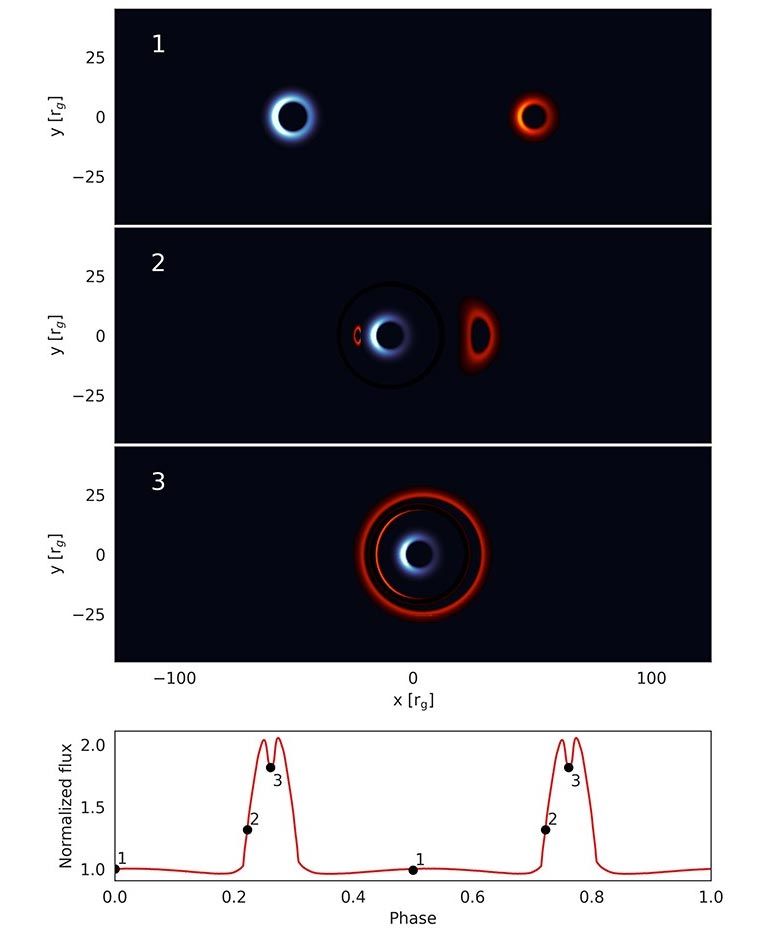

A gravitational lensing simulation in a pair of supermassive compact black holes. Credit: Jordi Devalar

This technique has only two requirements. First you need a pair of supermassive black holes in the midst of a merger. Second, you should look at the pair at roughly a side angle. From this side view, when one black hole passes in front of the other, you should be able to see a bright flash of light as the black hole’s glowing ring is magnified by the black hole closest to you, a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing.

The lens effect is well known, but what the researchers discovered here was a subtle signal: a characteristic dip in brightness corresponding to the background black hole’s “shadow.” This subtle dimming can last from a few hours to a few days, depending on the size of the black holes and the entanglement in their orbits. By measuring how long a drop lasts, the researchers say, you can estimate the size and shape of a shadow cast by a black hole’s event horizon, the no-escape point where nothing, not even light, escapes.

In this simulation of a pair of supermassive black hole mergers, the black hole closest to the viewer approaches and thus appears blue (box 1), causing the red-shifted black hole behind it to be magnified by a gravitational lensing. As the nearest black hole amplifies light from the farthest black hole (box 2), the viewer sees a bright flash of light. But when the nearest black hole passes in front of a gap or shadow of the farthest black hole, the viewer sees a slight decrease in brightness (box 3). This decrease in brightness (3) is clearly visible in the light curve data below the images. Credit: Jordi Devalar

“It took years and tremendous effort by dozens of scientists to get this high-resolution image of M87 black holes,” said study first author Jordi Davilar, a postdoctoral fellow at Columbia and the Flatiron Center for Computational Astrophysics. “This approach only works with the largest and closest black holes – the pair at the core of M87 and possibly our Milky Way.”

He added: “With our method, you measure the brightness of black holes over time and you don’t have to spatially resolve every object. It should be possible to find this signal in many galaxies.”

The black hole’s shadow is its most mysterious and instructive feature. “This dark spot tells us something about the size of the black hole, the shape of the spacetime around it, and how matter falls into the black hole near its horizon,” said co-author Zoltan Haiman, a professor of physics at Columbia University.

When a supermassive black hole merger is observed from the side, the black hole closest to the viewer enlarges the farther black hole through the action of a gravitational lens. The researchers detected a short dip in brightness corresponding to the “shadow” of the distant black hole, allowing viewers to appreciate its size. Credit: Nicoletta Parolini

The shadows of a black hole can hide the secret of the true nature of gravity, one of the fundamental forces in our universe. Einstein’s theory of gravity, known as general relativity, predicts the size of black holes. Hence, physicists have sought to test alternative theories of gravity to reconcile two competing ideas of how nature works: Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which explains large-scale phenomena such as planetary rotation and the expansion of the universe, and quantum physics, which explains how small particles such as electrons take Photons have multiple states at the same time.

Next, researchers became interested in igniting supermassive black holes Foreman A putative pair of supermassive black holes at the center of a distant galaxy in the early universe.[{“ attribute=““>NASA’s planet-hunting Kepler space telescope was scanning for the tiny dips in brightness corresponding to a planet passing in front of its host star. Instead, Kepler ended up detecting the flares of what Haiman and his colleagues claim are a pair of merging black holes.

They named the distant galaxy “Spikey” for the spikes in brightness triggered by its suspected black holes magnifying each other on each full rotation via the lensing effect. To learn more about the flare, Haiman built a model with his postdoc, Davelaar.

They were confused, however, when their simulated pair of black holes produced an unexpected, but periodic, dip in brightness each time one orbited in front of the other. At first, they thought it was a coding mistake. But further checking led them to trust the signal.

As they looked for a physical mechanism to explain it, they realized that each dip in brightness closely matched the time it took for the black hole closest to the viewer to pass in front of the shadow of the black hole in the back.

The researchers are currently looking for other telescope data to try and confirm the dip they saw in the Kepler data to verify that Spikey is, in fact, harboring a pair of merging black holes. If it all checks out, the technique could be applied to a handful of other suspected pairs of merging supermassive black holes among the 150 or so that have been spotted so far and are awaiting confirmation.

As more powerful telescopes come online in the coming years, other opportunities may arise. The Vera Rubin Observatory, set to open this year, has its sights on more than 100 million supermassive black holes. Further black hole scouting will be possible when NASA’s gravitational wave detector, LISA, is launched into space in 2030.

“Even if only a tiny fraction of these black hole binaries has the right conditions to measure our proposed effect, we could find many of these black hole dips,” Davelaar said.

References:

“Self-Lensing Flares from Black Hole Binaries: Observing Black Hole Shadows via Light Curve Tomography” by Jordy Davelaar and Zoltán Haiman, 9 May 2022, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.191101

“Self-lensing flares from black hole binaries: General-relativistic ray tracing of black hole binaries” by Jordy Davelaar and Zoltán Haiman, 9 May 2022, Physical Review D.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.105.103010

“Social media evangelist. Baconaholic. Devoted reader. Twitter scholar. Avid coffee trailblazer.”

More Stories

Ghost of Tsushima Director's Edition for PC – Cross-Play, Trophy Support, System Requirements, and More – SHOCK2

As a solo player, the expansion feels like it was made for me!

Researchers find a solution to the paradox surrounding Uranus and Neptune